Zzzap! How You Know When A

Book Will Be Finished

"Where do your ideas come from?" is supposedly the question writers are asked most often, although the question I've probably been asked most is "How much do you earn?" or, possibly, "When are

you going to write a proper book?" Maybe I should move in better circles.

I heard a new question for writers recently, while chatting with some writer friends. One was struggling with several drafts of an idea she loved but wasn't finding easy and asked,

plaintively, "How do you know when what you're noodling about with is going to be finished? At what point do you know you're not wasting your time and you're working on an actual book?"

We were floored for a moment. Then one of us offered the suggestion that if you could make it to, say, five thousand words on a project, that meant you were probably going to finish it. Some agreed, some disagreed. Some quibbled about the number.

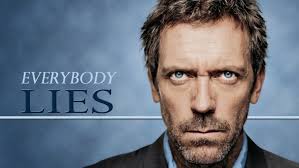

Personally -- and this is only a personal view because I long ago learned that there are almost as many different ways of writing as there are writers and if a method works for someone, anyone, then it's good -- but personally, looking back at my own work, I don't think it has anything to do with word number. A book of mine has never stumbled to its knees and died on the page in front of me because I've written too many or too few words. And if it's dying, flogging myself on to write a few more hundred words -- or cutting some out, for that matter -- has never saved one. (Forgive the life and death metaphor. I think I've binge-watched too many episodes of House recently. ('He's seizing! Quick!')

So, how do you know when the idea you're working on is going to be strong enough, engaging enough, interesting enough to make it through months, maybe years of work to become a finished

story or book? (And I include picture books and children's books in this, and non-fiction, which are no easier than any other kind of writing to do well, though, curiously, many people seem to

think they are.)

Well, first, I find it can be very hard to tell whether or not my present project has legs. I have abandoned several books after working hard on them for as long as a year. Why? I couldn't handle

the material, I couldn't find a conclusion that was 'big enough' or interesting enough to make it worth a reader's effort to plough through all the rest. Never a truer word was said than:

Endings Are A Bitch. I'd produce a series of cushions, mugs and mouse-mats featuring that motto except I fear that a quick internet search would show I've been beaten to it.

If you'll bear with me, it reminds me of something I read about Buster Keaton. The great actor/director loved devising screenplays around big technology, so what many think was his best film, The General, featured a young couple alone, on a fast moving steam train which they cannot stop (because their train is being chased by another train controlled by enemy forces.) Another, The Navigator, had a young couple as the only people on board a huge liner which is adrift on the ocean, due to similar hostile machinations. While inventing most of his visual gags himself (and they were often very dangerous), Keaton worked with screen-writers to come up with convincing plots -- that is, to put a framework that made some kind of sense around the stunts he was hell-bent on filming regardless. (Writing books is only different in that we work hard to contrive a plot that makes a sort of sense to frame the scenes we are hell-bent on writing, come what may.)

Keaton wanted to make a third film around technology, set in a giant skyscraper, which at the time, were still new and exciting engineering projects. He and his writing team came up with a story about a rich young man who lives at the very top of the highest skyscraper yet built in an apartment crammed with all the latest, exciting electrical gew-gaws. (This was 1924, nearly a hundred years ago.) When the electricity short-circuits, he is trapped (with the requisite pretty young woman). How will they escape?

Keaton and the writers, no matter how they tried, couldn't invent a satisfying, convincing plot that gave the young couple lots of stunts and adventures but ended with them safely back at street

level. After much effort, they eventually put the idea to one side. More time passed and the team split up to work on other projects. The skyscraper film was never made. Decades later, when

Keaton had long lost touch with the writers, he was seated in a hotel lobby when, by chance, one of the writers hurried past. Without breaking stride, the writer called, "Don't worry, Buster!

I'll get you down from that penthouse yet!"

Quite. You don't forget these ideas you have to give up on. They rankle.

But how do you know when a book is going to be completed instead of just petering out and hanging... for years? Well, for me, it's the zzzzap! I don't know how else to put it. The zzzzap

is a jolt of electricity, a light-bulb moment and when you feel that jolt and that bulb lights up, you know you're going to finish this one, no matter how long it takes.

Forgive me for using my Sterkarm books as an example again, but I happen to remember rather clearly how the first book, The Sterkarm

Handshake, progressed from a small idea that I sort of liked to something I was going to finish, though Hell itself should bar the way.

It began when I learned about the Border reivers on a walking holiday. I found them fascinating and felt strongly that I wanted to write about them -- but that wasn't enough. I could have

invented no end of characters, or borrowed them from history, but I had no plot. And anyway, I realised that a historical novel, set entirely in the 16th century with no reference outside it (or

no overt reference anyway) held no appeal for me at that time. I'd written historicals before, I just didn't feel any excitement about doing it again. So the problem became: How to write about

the historical reivers without writing a historical novel.

I played around with the idea of having 21st Century characters visit the 16th Century. After all, if a historical novel is always about the writer's own time, no matter how hard they try to be

'historical', why not be open about it and make a novel set in 16th Century Scotland about the 21st Century? That appealed a lot more and warmed the idea up considerably, but still wasn't

enough. I still had nothing but a notion and an interest wandering around in a fog.

I thought about ways to mix up the 21st and 16th centuries. I rather liked the idea of a time machine. (I always have liked the idea of time machines.) I considered who would fund a time machine

and decided that it would be a multinational company that wanted to raid the past for fossil fuels -- and that heated up my interest a good deal more: the eco-angle, the 'advanced society

colonising a less technological one' angle. But still not enough. I didn't want to launch into writing it because I felt it would keel over and die after a couple of chapters. (This fear

always haunts me when I begin something new. Later on comes the fear that no one will buy it.)

I did start inventing characters and scenes, though I didn't write anything down. I would think about it while I walked or rode on buses or at other times when I had nothing much else to do. Who

would the 21st Century characters be, who would the reivers be? I liked the whole idea, I was enthusiastic but still hesitated... Where could the story go? Y'know, 16th century characters meet

21st century characters, 21st century characters murder and exploit 16th century characters -- no surprises there. And there have to be some surprises in a novel.

While thinking about characters and possibilities, I wondered what each side of the time divide would think of the other. The 21st Century attitude was fairly obvious: they would think the

reivers primitive, dirty, violent and rather stupid because they didn't have whatever was the must-have gadget back in 1996, when I was doing this thinking. (Lord, how time flies.)

What would the reivers think of the 21st Century people? I imagined a landrover appearing on a Scottish hillside and people in jeans and parkas climbing out. A magical cart that moved by itself.

Would the reivers think it had come out of the hill? -- In Scots legend, the elves live under the hills and come out at Mayday, Midsummer, Hallowe'en and New Year, to 'ride.' The reivers would

think the 21st Century time-travellers were elves from under the hill.

Zzzzap! That opened up a whole new line of plot development by bringing in the folklore of the Borders. The reivers thought elves powerful but not unbeatable. They believed elves to

have magical powers but also very understandable jealousies, ambitions and sulks, which could be manipulated. If a reiver was taken on a trip into the 21st Century s/he would believe it was a

trip into ElfLand -- where they must not eat or drink the smallest amount or they would never be able to return to their own world.

The light-bulb in my head lit up so bright, I think the light probably shone out of my ears.

I'm not sure why it was this idea about the 21st Century people being thought of as elves that made the difference when other ideas didn't. I think it's a fairly common SF trope that's been used

by many writers before me, so I don't think its galvanising power lay in any originality but only in its personal appeal for me. With the arrival of the 'time-travellers as elves' idea, I had a

setting, a situation and a relationship between the characters. With one swoop, the idea connected up my new interest in the reivers with my lifelong interest in social history and folklore:

Zzzzap!

As C. S. Lewis put it: our writing develops from 'the permanent furniture of our minds.'

I know I'm going to finish a book when I get zapped. -- How do you know?

Some Other Books By Susan Price